UK-LATAM RELATIONS

CEO of Canning House Jeremy Browne discusses his new role and his belief that Latin America should be a significant part of the UK’s post-Brexit trajectory with Venetia van Kuffeler

New Chief Executive of Canning House Jeremy Browne is frank about the challenges he’s up against: “The biggest hurdle that we have to overcome is that Latin America is woefully neglected by Britain.” Back in June, the UK’s leading forum on Latin America appointed the former UK Minister of State for Latin America as its new CEO. Jeremy brings a wealth of government and business experience as well as ambition to Canning House’s mission to build understanding and relations between the UK, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Iberia.

Founded in 1943, the institution is named after George Canning, the early nineteenth-century Foreign Secretary who devoted much of his career to Latin America, simultaneously advancing the causes of greater Latin American independence and British commercial interests. Jeremy explains: “We are a global forum for thought-leadership and pragmatic debate on the region’s political, economic, social, health and environmental trends and issues - and their implications for business risks and opportunities.” Back in 2010, speaking at Canning House, then Foreign Secretary William Hague introduced the British government’s Canning Agenda, which pledged a wholesale revitalisation of the UK’s relationship with Latin America – to re-build economic relationships, tackle climate change, reinforce educational bridges, and provide Latin America with an international partner.

Growing up, Jeremy admits he “never knew anything other than a diplomatic life. My father spent his entire working life in the British Foreign Office, meaning my siblings and I had a public service, nomadic upbringing.” However, he found his way to the foreign office building “by a strange twist of fate” first by becoming a politician and then a minister of state. “I was elected as an MP just before my 35th birthday, and then re-elected just before my 40th birthday. The party I represented [Liberal Democrat] entered government for the first time since the second world war, and I became a minister in the Foreign Office in 2010.”

As it turned out about two-thirds of the world’s population was within my area of responsibility. I was otherwise known as Minister for Permanent Jetlag!

There his prime responsibility was for Britain’s foreign policy with most of Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. He wryly notes, “As it turned out about two-thirds of the world’s population was within my area of responsibility. I was otherwise known as Minister for Permanent Jetlag!” However, he found himself enthused, “as I felt that I was working in parts of the world where change was happening fastest. At the time, there was still considerable debate on how China would choose to play it in the future: would it integrate more with the West or set itself up as its rival? Of course, this conversation continues. Japan was still the third largest economy in the world, but then came the tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, which was a massive blow to Japan’s economy and psychology.”

He admits that at the time he “had no first-hand experience of Latin America, but it was a great opportunity to do something without any fixed preconceptions. My job was to provide the momentum and enthusiasm that the foreign secretary was seeking for his new vision for the UK and Latin America.” This involved travelling a huge amount: “I went to the inauguration of the Colombian President and met Chile’s new President. I travelled to Ecuador, Bolivia, Uruguay, Guatemala and Costa Rica, among others. Many of these countries had not had a British ministerial visit for at least a decade. The very act of turning up was a clear demonstration of intent and interest.”

Jeremy’s task and wider mission at Canning House “is to try and raise consciousness about Latin America in Britain. We tend to focus on the negative issues associated with the continent: corruption, natural disasters, displacement of indigenous people, drug smuggling etc. But we should focus on the fact it is a positive place of opportunity.” He continues, “Canning House needs to have less of the feel of an NGO leaflet, and more the feel of a Financial Times editorial. We need to be more business orientated and think about the opportunities that will also exist in Britain if we forge stronger relationships with Latin America.”

He concedes he is up against some major challenges. Back in 1808, 40 per cent of British exports were bound for Latin America; by 1914, 50 per cent of foreign investment in the region came from the UK, and 20 per cent of its trade. However, in the aftermath of World Wars I and II, UK attention turned elsewhere; and, by his foreign office appointment in 2010, trade and investment had plummeted to barely 1 per cent and 5 per cent respectively. Today, he notes, “Everyone understands that the FCDO is going to devote a lot of time to Ukraine, our relationship with the EU, the US and so on, but as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, the UK has a genuinely global outlook and disposition. It is reasonable to ask what the British government’s ambitions for our post-Brexit relationship with this continent will be. It’s a hard question to answer, because the British government, Parliament and business focuses very little attention on Latin America.”

It is reasonable to ask what the British government’s ambitions for our post-Brexit relationship with this continent will be. It’s a hard question to answer, because the British government, Parliament and business focuses very little attention on Latin America.

However, Jeremy believes there are many reasons for a reasonably well informed, internationally minded business in Britain to be interested in Latin America. “There are opportunities in mining, energy, infrastructure, technology, professional (financial, legal, consultancy) services, fintech and agribusiness. There are lithium reserves in countries like Bolivia, copper in Chile and many of the raw materials needed for electric cars will come out of the ground in Latin America. Aside from traditional energy, like oil in Brazil and Venezuela, Chile’s new Ambassador recently explained that their unique geography puts them at an advantage. Stretching from near to the equator down to the Antarctic Circle, Chile has reliable solar power in the north, a long coastline to provide a huge wave energy opportunity, and climate in the Andes can provide reliable wind power. Indeed, Chile is closer to its Net Zero targets than Britain or any of its European counterparts.”

In terms of agribusiness, he continues “whilst the global population is about to topple over eight billion, countries like Argentina produce ten times more food that it consumes, and there is potential to produce even more. Latin America is a big continent with a climate that is conducive to producing high quality food, without harming the wider environment. Latin America can be even more part of the conversation about global food supply.”

In terms of climate change, Jeremy notes “Latin America has a lot of knowledge and expertise on the matter. There is a deep sense of connection between Latin Americans and their natural environment. Their embrace of environmentalism is a natural tendency, rather than feeling like a political issue. We also have a lot to learn from each other. Latin America and Europe have a natural meeting of minds on the climate change agenda. There is a genuine two-way conversation to be had.”

Whilst the global population is about to topple over eight billion, countries like Argentina produce ten times more food that it consumes, and there is potential to produce even more.

His enthusiasm for the continent is palpable. “By and large, Latin America has embraced a western political sentiment: there are elections, presidents, parliaments, open civic societies and free media. Although it’s not perfect, it is accepted that these are the building blocks of society, which is certainly not the case all over the world.

“In Latin America the trajectories are greater than Europe economically, and in demographic terms, so there is a good argument to be mindful of the opportunities that exist beyond our own continent. There is goodwill and room for growth in our relationship. Britain is widely respected and there are huge historical connections, but we are less present in the day to day lives of Latin American decision makers that we could be.”

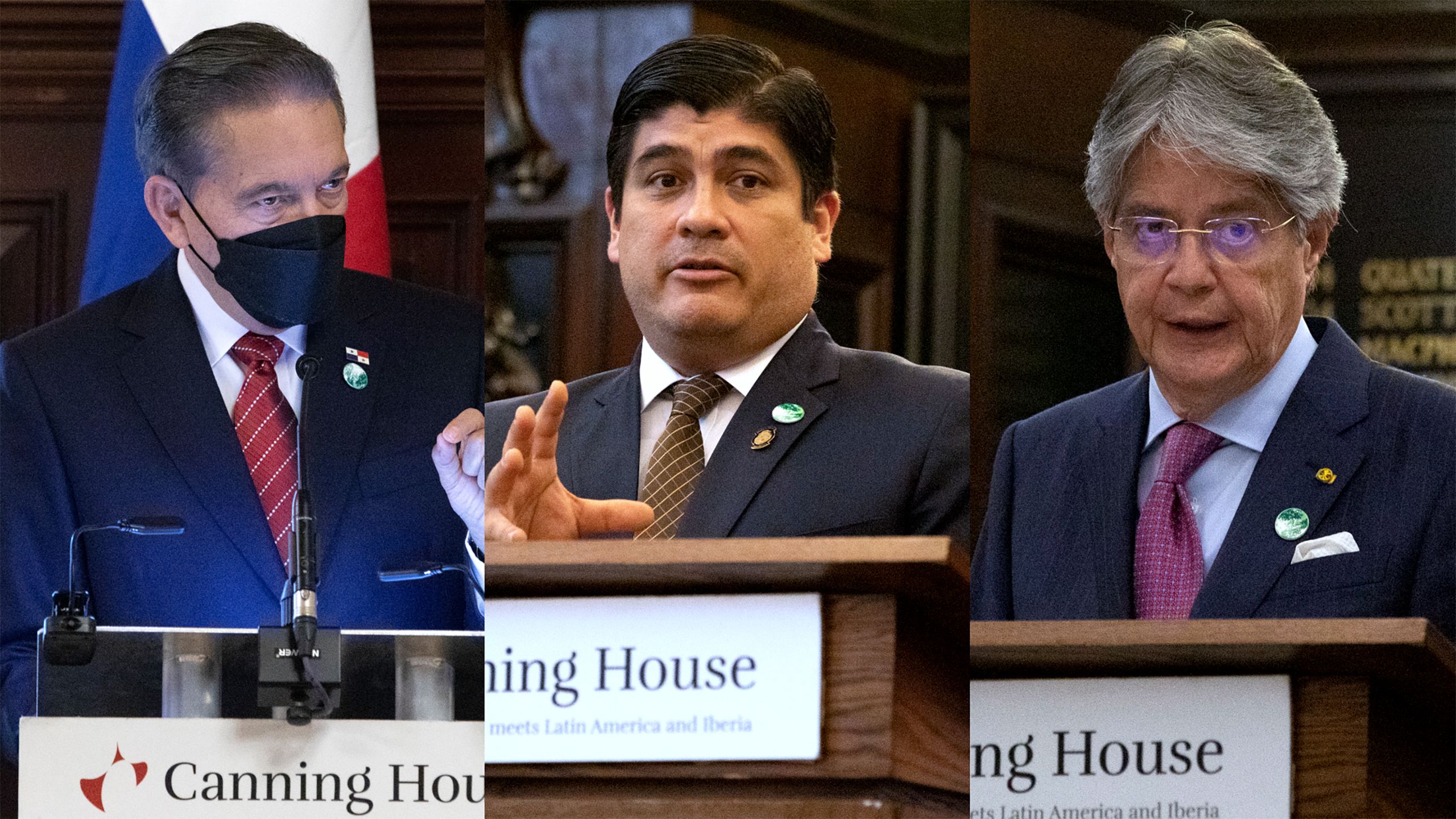

This summer, his new role has involved a whirlwind tour meeting the Latin American Ambassadors accredited to the Court of St James’s. “London’s diplomatic community is an important network for us because we want to be the go-to institution, network and organisation that is hosting top-quality events on Latin America. Of course, there’s a mutual interest, as we can provide access to networks in London and a platform for visiting Latin American ministers, prime minister and presidents. Spain and Portugal are also part of the wider Canning House family.”

So what’s new for Canning House over the next decade? “A new Prime Minister and government should provide a reset in British politics. The slower burning issue is how Britain seeks to define its post-Brexit role. I believe that Latin America has got to be part of that equation. If the new Foreign Secretary were to give a speech on what Britain’s place in the world would look like in 2032, my hope is that Latin America should feature heavily.”