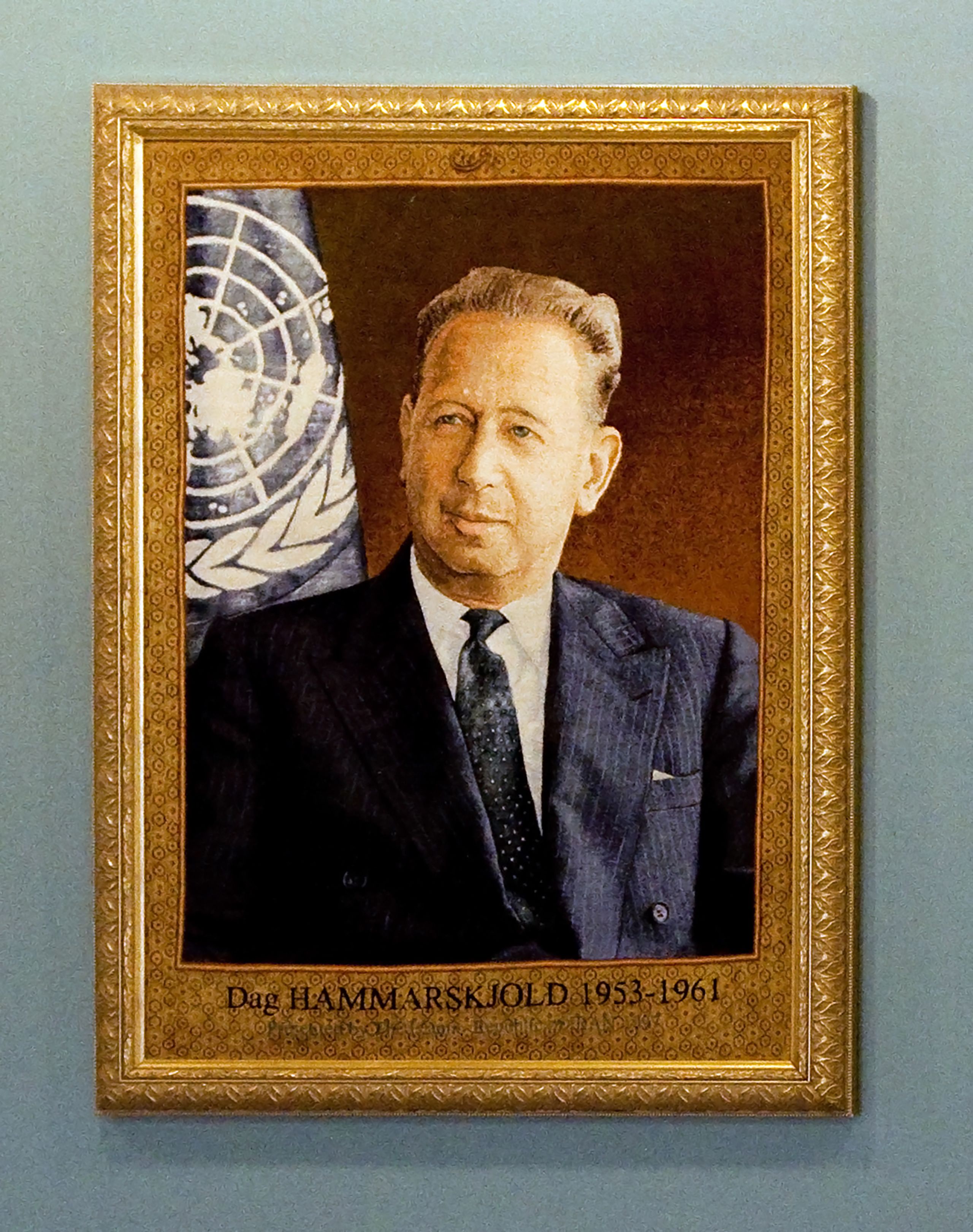

The Cold Case of former UN Secretary General, Dag Hammarskjöld

Harold Cluff reports on

the most enduring mystery in modern diplomatic history

At around midnight on the 18 September 1961, a bright flash illuminated the sky over the North Rhodesia-Congo border. Fifteen hours later, search and rescue teams converged on a crash site. In the midst of the jungle, they discovered the wreckage of an aircraft chartered to convey the UN General Secretary, Dag Hammarskjöld, into the Katanga region of Congo. His mission was to negotiate a ceasefire between the Katanganese secessionist forces backed by Belgian troops and the Congo central government in Leopoldville. Of the 16 passengers and crew on board, only one was found alive, but he succumbed to his injuries several days later. He lived long enough to tell investigators what he had heard and seen. According to the passenger, there was a bang, a blast, Hammarskjöld shouted “Turn back! Turn back!” then all was black.

In the wake of the tragedy, President Kennedy passionately lamented the loss of Hammarskjöld whom he described as the ‘greatest statesmen of the century.’ The debonair Swedish diplomat’s unexpected demise stunned both sides of the burgeoning Congolese civil war. Their mutual shock incited a sudden ceasefire. In his last effort, Hammarskjöld was to some extent successful, albeit at the cost of his life. The cause of the youngest ever UN General Secretary’s dramatic death remains a baffling mystery. After dozens of independent and UN-based inquiries, official investigations are still ongoing. Many compelling explanations and credible theories abound. If Hammarskjöld’s plane was purposefully shot down, blown up or sabotaged, no culprit has ever been held officially responsible.

In his last effort, Hammarskjöld was to some extent successful, albeit at the cost of his life. The cause of the youngest ever UN General Secretary’s dramatic death remains a baffling mystery.

Dag Hammarskjöld was the youngest son of the Prime Minister of Sweden. He grew up in a cultured household where the virtues of public service and religious piety were expounded and extolled impressively by his accomplished and cultivated parents. His precocious abilities impressed his peers and teachers so much that his father once joked that if he had half of Dag’s brains, he would have gone far. Via his distinguished career as an economist, he learned the trade of diplomacy, earning respect from politicians and policymakers across Europe for his prescience and perspicuity. As the second ever UN General Secretary, he had to contend with the complexities of the Cold War, seeking compromises between the dualling superpowers while advocating on behalf of smaller unaligned countries and nascent nation states. As a result, he often played a starring role in the high drama of world politics in the 1950s.

While he fought ferocious battles in the UN general assembly, delivered grand declarations about justice in an unjust world and applied his problem-solving powers to intractable riddles, he wrote hundreds of philosophical meditations and aphoristic poems, the collection of which was published posthumously and given the title Markings. His friend, the poet WH Auden, translated them into English. While there are no direct references to the crises he had to manage or the events he had to endure, Markings is still an informative read. It reveals an intellect steeped in Christian thought and a character acutely sensitive to the moral quandaries a life of energetic public service engenders. It is the eloquent work of a latter-day mediaeval mystic concerned with the tumult and turmoil of international affairs. Loneliness is a recurring theme throughout the book. An individual who devotes themselves to untangling skeins and skeins of gordian knots can’t help but feel alone, especially if, as with Hammarskjöld, they are unmarried and romantically unattached.

The last leg of Hammarskjöld’s roller coaster career was certainly a crescendo on a symphonic scale. The withdrawal of Belgian administrators from the Congo in 1960 precipitated the disintegration of civil order. The semi-autonomous resource-rich Katanga region felt more aligned with North Rhodesia than the rest of the Congo and its leadership steadfastly pushed for secession. The controversial Prime Minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, repeatedly hinted at his close association with the Soviet Union in front of the world press, unsettling the Americans. He favoured Congolese unity over confederation or Katangese independence. He was pitted against Moïse Tshombe - the urbane prime minister of the seceded Katanga state. Tshombe used Belgian troops to maintain his region's autonomy, thereby offending the treaty of independence signed between Belgium and the Congo in 1960. Hammarskjöld proposed the deployment of 4,000 UN peacekeeping troops to the Congo to provoke the withdrawal of Belgian troops from Katanga and to preserve the rickety infrastructure headed by the government in Leopoldville. Tshombe barred the entry of the UN peacekeeping force into Katanga, framing it as an act of intimidation by the Congolese central government. He did however acquiesce when Hammarskjöld offered to visit the region himself. Hammarskjöld’s death enroute to meet Tshombe stunned both factions in the brewing conflict causing the combatants to temporarily suspend hostilities.

Theories range from a mechanical malfunction downing the plane to a bomb being stashed onboard to the plane having been shot down by a pilot in the employ of Belgian industrialists with interests in Katanga. The case remains open and has intrigued droves of investigators over the decades. A few years ago, a former NSA officer recounted his experience of that night. In the early hours, he was called into his office to listen to a recording of a mercenary pilot known to the NSA. The voice on the recording said “I can see the plane. I am going in.” After the rattle of gunfire, the voice continued “I have hit it. It is going down.” The voice is thought to be that of a Belgian-born British pilot called Jan van Risseghem. He flew spitfires for the RAF during World War II. His post-war life was similar to many ex-military Europeans in West Africa - that of a soldier of fortune or gun for hire. Some have accused the mining company Union Miniere of ordering the hit because of the threat Hammarskjöld posed to their interests in Katanga. To this day, no one has been held responsible for the death of Hammarskjöld, making it the most enduring mystery in modern diplomatic history.

As the second ever UN General Secretary, he had to contend with the complexities of the Cold War, seeking compromises between the dualling superpowers while advocating on behalf of smaller unaligned countries and nascent nation states.

After several immediate inquiries, the UN reopened the case at the behest of noted jurists and independent investigators and concluded that there was a possibility that Hammarskjöld’s plane might have been downed by hostile engagement from another aircraft or a bomb. In 2019, the UN released the findings of their most recent report on the incident, saying: “Advancements have been made in the body of relevant knowledge, most notably in the areas of the probable intercepts by Member States of relevant communications; the capacity of the armed forces of Katanga to have staged a possible attack against the Secretary-General’s plane; the presence in the area of foreign paramilitary and intelligence personnel; and other information relevant to the context and surrounding events of 1961.”

We might not know why the plane crashed, who may have attacked it or for what reason, but we do know that Hammarskjöld was fully aware of the price his line of work required him to pay. In an early entry in Markings he wrote: “Tomorrow we shall meet/death and I/and he shall thrust his sword/into one who is wide awake.” When former British Prime Minister Pitt the Younger was told by his physician that he had to resign from the premiership and go into early retirement if he wanted to live a normal life span, he replied: “I would rather die at my post than abandon it.” That appetite for self-sacrifice is all too rare in public life. Hammarskjöld knew what his role as a ‘secular pope’ and ‘yogian commissar’ entailed. For his selflessness and zeal he deserves to be remembered, honoured and emulated.