Nigeria’s emerging leadership role in West Africa

Director of the Centre of Commonwealth Affairs, Sam Bidwell, reflects on how this emerging powerhouse within the region, is

also a country long overdue for international reappraisal

Slowly but surely, Western commentators have been forced to grapple with China and India’s emergence as global actors.

However, less widely-recognised is Nigeria’s emergence as the powerhouse of West Africa. In 1980, the country had a GDP of just US$64.2 billion; today, it is a top 40 global economy, with a GDP of more than US$450 billion. By 2050, PwC projects that this figure will stand at more than US$4 trillion, almost on a par with the UK.

The United Nations predicts that, by the same year, Nigeria will be the world’s fourth most populous country, bringing up the rear behind China, India, and the United States. Shortly afterwards, it will overtake the US and take a position on the podium as the world’s third most populous country. Already, the country is the world’s fourth largest Anglophone nation, and Africa’s largest economy. Lagos State alone is the continent’s eighth largest economy, outstripping countries like Ghana and Tanzania.

Given shared membership of the Commonwealth, common use of the English language, and compatible legal systems, Britain should be well-placed to support this emerging behemoth, in the mutual interest of both parties. As British investors seek out opportunities in emerging markets post-Brexit, Nigerian businesses are hungry for forex; pairing the vast capital reserves of the City of London with vibrant Lagos could prove to be a powerful combination.

More and more, Britain’s domestic priorities are downstream from events in Nigeria. Whether we’re talking about migration, restitution of colonial artefacts, or global climate change, there is a growing sense that the fortunes of Western Europe are tied intimately to West Africa.

At the same time, a growing Nigerian diaspora community in the UK provides a living bridge between London and Lagos – and further afield – which has the potential to supercharge the cultural ties between the two countries.

And yet, all too often, it feels like the relationship between Britain and Nigeria is far from reaching its full potential.

In October, I visited the country in my capacity as Director of the Centre for Commonwealth Affairs, accompanied by Ms. Abimbola Okoya, a member of the Centre’s Advisory Board and a former President of the Nigeria-Britain Association. Splitting our time between Lagos and Abuja, we spent a week speaking to more than a hundred stakeholders, over a series of five roundtable discussions which focused on key sectors of mutual interest.

These discussions provided fascinating insights into Nigeria’s political landscape, its fast-growing economy, and its perspective on the UK. They also highlighted the need for policy change in this country as regards our approach to Nigeria.

Wherever we went and whoever we spoke to, two realities were clear.

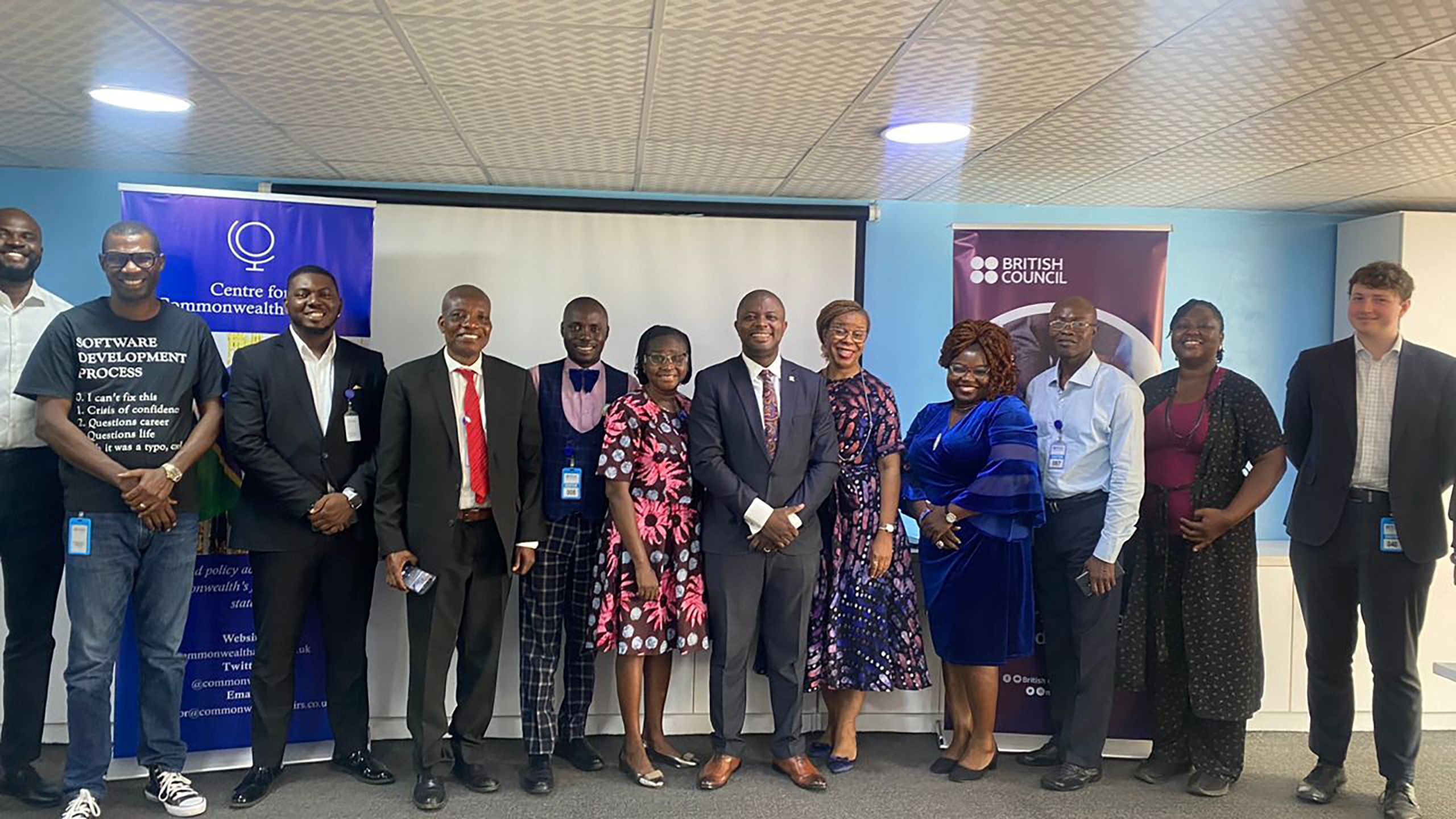

Meeting with education practitioners at the British Council on 10 October 2023

Meeting with education practitioners at the British Council on 10 October 2023

First, there was a pervasive sense that Britain is a trustworthy partner, which can be trusted over and above our European counterparts, and certainly over the ever-encroaching Chinese. There is a great deal of interest in forging new commercial and investment relationships with the UK, and the Commonwealth retains a reputation for fairness and reliability.

When we sat down with the Manufacturers’ Association of Nigeria Export Group (MANEG) in Lagos, every single business that we spoke to was keen to access the UK market and was delighted to hear about the ambitious tariff-reduction measures that the UK Government has undertaken through the Developing Countries Trading Scheme. MANEG’s new chair, Odiri Erewa-Meggison, has set out an ambitious plan to boost the country’s non-oil exports, and regards the UK as a priority market.

This sentiment was echoed at the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN), in Abuja. We heard about SMEDAN’s work in empowering SMEs to expand through exports, and about the sterling work undertaken by Dr Olawale Anifowose at the Enterprise Development Centre in Lagos. We also heard the same story again – every single business, whether they worked in food processing or fashion, saw the UK as an appealing, high-yield market.

Second, there was a feeling that the UK had been absent in recent decades, and sluggish to react to the great upheavals that Nigerian society has seen over the past 20 or 30 years.

Meeting with British High Commissioner to Nigeria in Abuja on 12 October 2023: Phil Hall, Abimbola Okoya, British High Commissioner to Nigeria HE Richard Montgomery and author of the article, Sam Bidwell

Meeting with British High Commissioner to Nigeria in Abuja on 12 October 2023: Phil Hall, Abimbola Okoya, British High Commissioner to Nigeria HE Richard Montgomery and author of the article, Sam Bidwell

There was a pervasive sense that Britain is a trustworthy partner, which can be trusted over and above our European counterparts, and certainly over the ever-encroaching Chinese

When we sat down with Providus Bank at their newly built headquarters in Lagos, we were struck by how slow the UK financial services sector had been to react to Nigeria’s emerging finance and fintech sectors. Challenger banks and fintech start-ups are subject to cumbersome, restrictive regulation, particularly around correspondent banking and EMI licensing. Cross-border payments are slow, and UK banks have not updated their risk profiles to reflect the current realities in-country.

There is also a sense that membership of the Commonwealth has not always conveyed enough material benefits on ordinary Nigerians to justify the price of admission.

The British presence on the ground, whether through the Foreign Office or through the British Council, is doing admirable work – but without a vote of confidence from Whitehall, budgets will remain tight, and focus will remain elsewhere.

And yet with the limited resources that are available, people like British Council country director Lucy Pearson are managing to have an outsized impact on shaping this relationship. At roundtable discussions on education and the creative industries, I was impressed with the British Council’s work in bringing together experts and practitioners to explore these areas of mutual interest. With even greater support, and a recognition from civil servants that the Nigerian relationship could be key for Britain’s Africa strategy, it’s easy to see how the UK could play a role as Nigeria’s go-to partner for upskilling, technology, and technical cooperation.

The Centre is currently in the process of producing a white paper on the UK-Nigeria relationship, which will expand on some of these key challenges, and set out tangible steps for updating and improving the relationship as it currently stands. We hope that, in our own small way, we can contribute towards changing attitudes and changing material realities, helping to bring this critical relationship into the twenty-first century.

It often seems like British commentators were blindsided by the rise of both China and India, leaving them ill-equipped to navigate shifting global sands. We must not make the same mistake with Nigeria. Though it is often said that the twenty-first century will belong to Asia, it could also see the full emergence of Africa onto the world stage – Britain must prepare itself for this new global reality, or risk being left behind.