Diplomacy and the Media

Diplomacy and the media can have a rich, mutually beneficial relationship – but don’t always. Diplomats should build media skills, explains Her Majesty’s former Ambassador to Austria and Ukraine, Leigh Turner

My first TV interview

I gave my first TV interview, in Russian, in August 1994. I was First Secretary (Economic). My colleague and I flew from Moscow to Khabarovsk, near the Chinese border in Eastern Siberia. After visiting local businesses and officials, being poisoned by samogon home-made vodka on a ferry trip on the mighty Amur river and declining an offer to go bear-hunting in the north for a bargain $1,600 a week, we climbed aboard the Trans-Siberian railway for the 14-hour trip to Vladivostok.

In early 1990s Russia, the railway system was one of few things that worked reliably. Our train rolled into the home of the Russian Pacific Fleet, only recently opened to foreigners, dead on time. Bleary-eyed and unshaven, I descended from the carriage to find myself surrounded by journalists and TV cameras, seeking Russian-language interviews. I did my inadequate best.

Media lessons for junior diplomats

The experience taught me three things. First, as a young diplomat, you should seize every opportunity for a live interview. The more junior you are, and the further from HQ, the less chance any screw-ups will have repercussions. Second, interviews are a two-way street. Our dawn efforts in Vladivostok sparked interest. A meeting with the controversial governor of the Far East Maritime Region, Yevgeny Nazdratenko, materialised. Third, most journalists, with a few notorious exceptions, want an interview to run well. If your interviewee comes across as an idiot, why are you interviewing them?

At that time, visits to zones of Russia previously off-limits to diplomats often generated coverage. On my first visit to Vladivostok in June 1993, when local journalists probed me on what intelligence (sic) we were collecting, the Russian Army newspaper Red Star published a report headlined “Vladivostok becomes a Mecca for foreign delegations”. After a visit to Tartarstan in 1994, Tatarstan News published a lengthy interview with me headed: “Leigh Turner: the economy of Tatarstan is stable.” When I visited Sakhalin Island in 1995, the English-language Sakhalin Newsran a front-page spread headlined: “Leigh Turner: Development of Russian economy surpasses statistics”. This was certainly true, in one way or another.

On my first visit to Vladivostok in June 1993, when local journalists probed me on what intelligence (sic) we were collecting, the Russian Army newspaper Red Star published a report headlined “Vladivostok becomes a Mecca for foreign delegations”.

A rich, symbiotic relationship

Diplomats and the media can have a rich, symbiotic relationship. Both hunger for information. Both, however much evidence may appear to stack up to the contrary, are human beings.

That interdependence between diplomacy and the media was perhaps closest on my 1992-5 posting to Moscow. In the 1990s, diplomats and journalists struggled to interpret events as communism and authoritarianism collapsed and regrouped. The Ambassador held lunches with the UK press corps in the ex-sugar baron’s mansion that was the residence, opposite the Kremlin. At one such event many speakers bemoaned the fact that the Communists, ejected from power in 1991, threatened to do well in upcoming elections. It took John Kampfner, then bureau chief of the Daily Telegraph, to point out that this system was called democracy.

In all my experience of diplomacy and the media, the worst press behaviour I witnessed, prophetically, came during the 1986 visit to Vienna of the Prince and Princess of Wales. I was responsible for handling the media, and rode my bike, black-tied, to the evening banquet at the City Hall. My efforts were in vain. A fist-fight broke out among photographers between those with good camera positions to capture “Lady Di” and those less fortunate.

Nor shall I ever forget the scolding I received from magisterial, legendary journalist Hella Pick for failing to admit her to the Ambassador’s residence in Vienna to use his private phone.

My First Interview

I gave my first ever interview on 12 November 1984 in Vienna. I had been out of the Embassy buying my lunchtime belegtes Brot (open sandwich) when a bomb exploded in the entrance to the consulate, in those days shielded only by an unlocked door designed to give easy access to members of the public. Luckily, no-one was injured.

The local English-language ‘Blue Danube Radio’ interviewed me. Who, they asked, might be behind the attack? I declined to speculate. What about off the record? the interviewer pressed me. I said the same thing. When transmitted, the repeated question was edited out of the interview. Years later, as Ambassador in Vienna, I agreed to talk to a respected journalist who interviewed me about a range of policy issues before slipping in a question about intelligence, on which I said I could not comment. He later used – only – my “no comment” as if I had been responding to a question in a documentary he had made on an entirely separate subject.

The key lesson here is: choose your words carefully to reduce the risk that later editing will twist what you say.

Interview techniques

Diplomats should explore the practice of journalism. Seize every training opportunity. Wherever you are posted, disasters will happen. As a potential contact point or crisis leader for every type of tragedy, you will sleep better once the building blocks of a press statement or response to media enquiries are lodged in your head. In a crisis, pity for the victims, praise for the first responders and a promise to help may sound mechanical, but when chaos surrounds you, structure helps. Other tips – from acknowledging the existence of the camera team as well as the interviewer, through not touching your face during an interview, to grounding your feet on the floor, can be transformative.

Diplomacy and social media

Whether a diplomat should go a step further and proactively create media content is a personal decision. An understanding of the mechanics of writing a newspaper article or blog is valuable for anyone trying to catch the attention of readers with a short piece of prose. Few diplomats will write regularly for a newspaper, as I did for the Financial Times from 2003 to 2006 in Berlin. But the experience shaped my subsequent career.

Many diplomats build a social media profile. Like learning languages, this comes more naturally to some than to others. Not everyone feels comfortable with the investment of time, the loss of privacy and the quest for content that comes with a commitment to Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter, Instagram etc. The 2020s may have seen the high tide of tweeting and blogging ambassadors recede from the risk-tolerant free-for-all of the 2010s, when social media was a part of my routine in Kyiv, Istanbul and Vienna.

Social media may be valuable for a diplomat. But it’s one communications tool among many – from a chat over coffee to a speech, a cocktail party or, if you are lucky, an evening’s carousing with a minister, a journalist or an artist. You have to do all of them!

What to Do Next

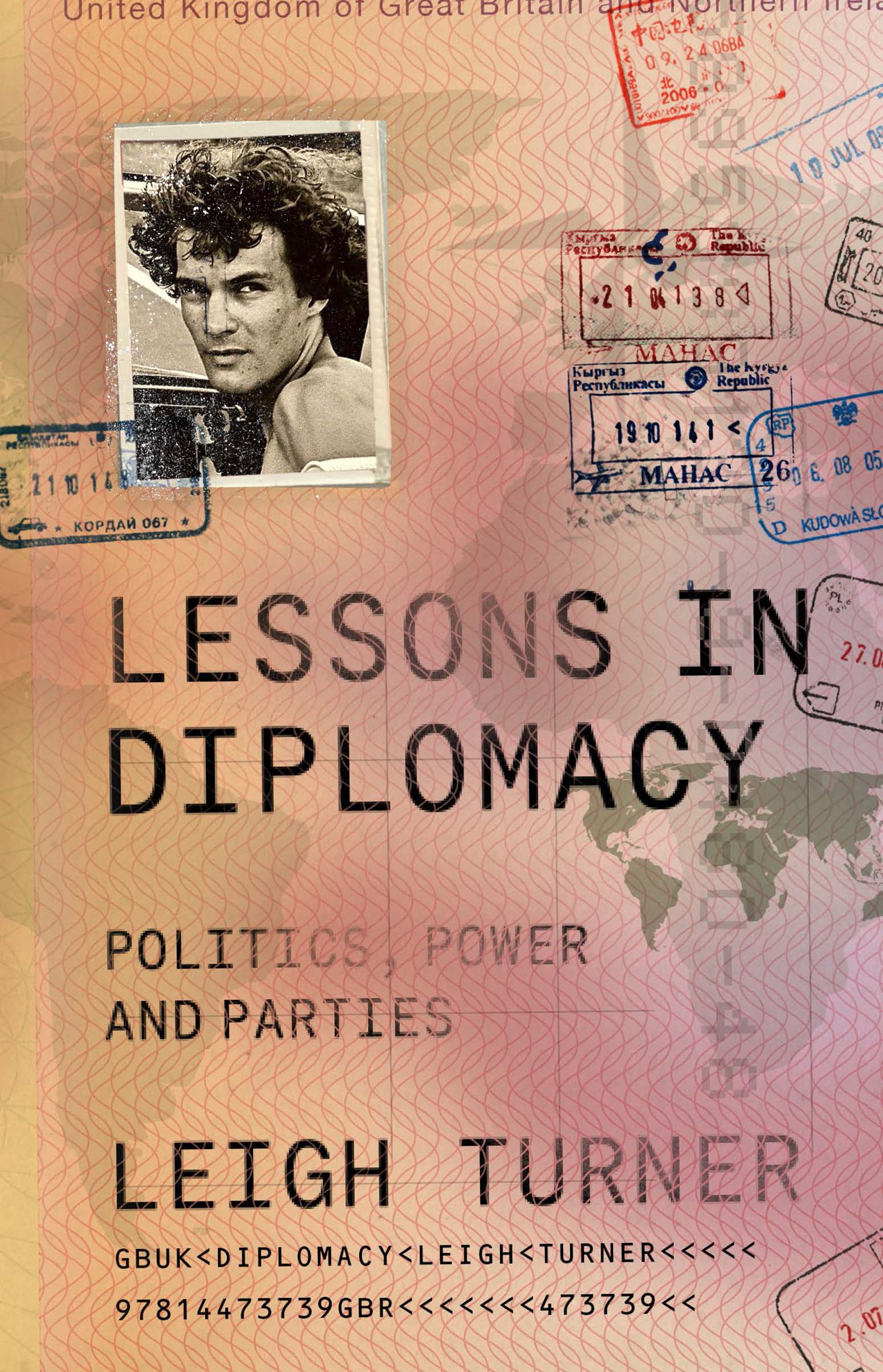

You can read more about Diplomacy and the Media in my book Lessons in Diplomacy: Politics, Power and Parties (Bristol University Press, 2024). It includes a whole chapter on How to be interrogated.

Leigh Turner is writer based in London. He was HM’s Ambassador to Austria and UK Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Vienna from September 2016 to September 2021. Leigh's previous roles were as HM Consul General Istanbul and Director General for Trade and Investment Turkey, Central Asia and South Caucasus; HM Ambassador in Kyiv, Ukraine, and Director of Overseas Territories in London, responsible for territories including St Helena, the Falklands and Bermuda.

Leigh grew up in Nigeria, Exeter and Lesotho, before education in Swaziland, Manchester and Cambridge. Leigh had a 42-year diplomatic career, lessons from which he draws in his September 2024 book Lessons in Diplomacy. He is the author of three thrillers and Seven Hotel Stories, a collection of feminist black comedies, and is a former writer for the Financial Times. He lectures at the Oxford University Diplomatic Studies Programme, the LSE, Vienna University and the Danube University Krems, and is a Visiting Professor at Graz University.]