A SHIFT IN APPROACH TO GENOMICS

Founder and Chair of the Global Genomics Programme at the independent policy institute Public Policy Projects, Kate Orviss, explains why we all need to be aware of genomics and the important role the diplomatic community has played and can play in seeking to bring the benefits of genomics to all citizens of the world

What is genomics? So often the answer to that question can quickly get into the detailed science or technology of genomics or starts a discussion about Crick & Watson (or perhaps more pertinently Rosalind Franklin) and the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA or sequencing and base pairs and variants and mutations and other -omics. This can be challenging. And unnecessary for most of us.

In essence genomics is how we understand what it means to be a living organism by understanding all the genes and DNA of that organism. This is in contrast to genetics which focuses on the understanding of individual genes. Genomics marries biology with statistics and computational science and researchers in the original Human Genome Project (on which see further below) compared their feat to the Apollo moon landing and splitting the atom. Which means genomics is a very big deal for biology.

The reach of genomics is vast and almost every aspect of our lives has a genomics component – from pathogen surveillance (as we all saw during the pandemic when we heard a lot about genomics, probably for the first time for many of us) to more precise human healthcare (including rare disease diagnosis by understanding the impact of variants in certain genes) but it also has application in relation to biodiversity, climate change, agriculture, forestry our oceans and One Health more generally.

The Human Genome Project was instigated in the US in October 1990 but involved an international and open collaboration between nations from the outset. It sought to produce the first draft of the human genome – what has been described as the most wondrous map ever created. It was not a Project without challenge or controversy; it took a long time and cost a huge amount of money and it took significant diplomatic intervention to proceed.

In 2000, in a carefully choreographed event at The White House and, via video link, 10 Downing Street, the first rough draft of the human genome was announced by President Bill Clinton (incidentally the full first draft wasn’t completed until 2003 and only very recently has the full genome been sequenced). Right from the outset President Clinton was clear that “We must ensure that new genome science and its benefits will be directed toward making life better for all citizens of the world, never just a privileged few.”

And yet in 2024, notwithstanding the incredible advances made in the field (including sequencing now being possible for a tiny fraction of the time and cost of the original effort), the benefits of genomics in the field of human healthcare are not felt by all citizens of the world and in part this is driven by a lack of diversity in the underlying datasets and the wider genomics ecosystem.

Genomics will, therefore, exacerbate health inequalities globally.

Right from the outset President Clinton was clear that “We must ensure that new genome science and its benefits will be directed toward making life better for all citizens of the world, never just a privileged few.”

Genomics in the field of human healthcare has the potential to bring great healthcare benefits – better diagnosis of rare disease, more precise medical interventions, population health screening and the ability to better understand the efficacy of drugs and to seek to avoid adverse drug reactions (which is called pharmacogenomics) – but if the understandings and applications are derived from data which is not representative of all of our populations then these benefits will not be felt the same everywhere. We know a marker for a rare disease in one population may not be so in another.

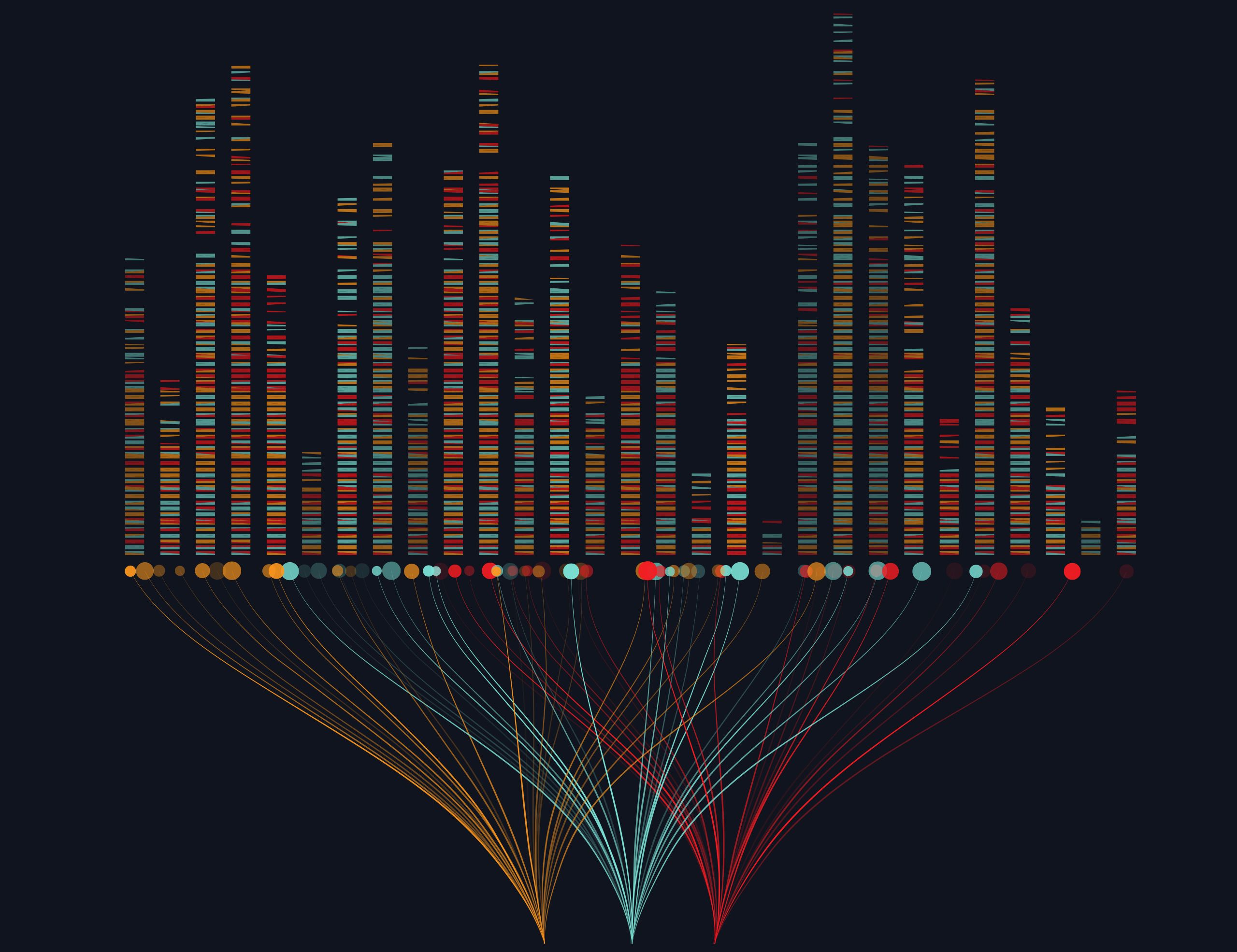

Genomics is one colossal team sport as no one country, research organisation, company, clinician or patient can achieve the full potential of genomics in isolation. It relies on the ability to compare data and the more data the better. However, currently approximately 80 per cent of the data globally is derived from people of European ancestry. Some nations and communities will not be represented in the global datasets at all. And the proportion of data from Africa is actually getting smaller as a proportion of the whole global dataset as sequencing is taking place so quickly elsewhere.

But it shouldn’t just be about data – if we only focus on collecting more diverse data (which is the focus of many discussions and is clearly important) then I feel we are in danger of adopting a stamp collecting approach. Diversity needs to be about diversity in the whole ecosystem. This doesn’t just improve our understanding of human healthcare, it also creates opportunities for economic growth more widely. It should not just be for those jurisdictions with advanced genomics ecosystems to derive greater benefit from what could be achieved – we need to see greater collaboration, greater skills and knowledge transfer and more capacity building. We also need to see all populations, including Indigenous Peoples, Minority Populations and Underrepresented Communities being properly and respectfully included. And once we have data we need to make sure that we do something meaningful with it to ensure that everyone can have the same opportunity to access the benefits of genomics.

Genomics in the field of human healthcare has the potential to bring great healthcare benefits – better diagnosis of rare disease, more precise medical interventions, population health screening and the ability to better understand the efficacy of drugs and to seek to avoid adverse drug reactions

This all requires a shift in approach – if we just do what we’ve always done then we can’t expect a different outcome. We have a tremendous opportunity to make that shift in 2024 and beyond and the diplomatic community has a very significant role to play through understanding the challenges and the opportunities and making the connections that need to be made to advance engagement with policymakers wherever possible.

To hear more about these issues and join the conversation please join us at the third Public Policy Projects Global Genomics Conference at One Great George Street, London on 20 November 2024.